Does Market Timing Work?

Imagine for a moment that you’ve just received a year-end bonus or income tax refund. You’re not sure whether to invest now or wait. After all, the market recently hit an all-time high. Now imagine that you face this kind of decision every year—sometimes in up markets, other times in downturns. Is there a good rule of thumb to follow?

Our research shows that the cost of waiting for the perfect moment to invest typically exceeds the benefit of even perfect timing.1 And because timing the market perfectly is nearly impossible, the best strategy for most of us is not to try to market-time at all. Instead, make a plan and invest as soon as possible.

Five investing styles

But don’t take our word for it. Consider our research on the performance of five hypothetical long-term investors following very different investment strategies. Each received $2,000 at the beginning of every year for the 20 years ending in 2020 and left the money in the stock market, as represented by the S&P 500® Index.2 (While we recommend diversifying your portfolio with a mix of assets appropriate for your goals and risk tolerance, we’re focusing on stocks to illustrate the impact of market timing.) Check out how they fared:

- Peter Perfect was a perfect market timer. He had incredible skill (or luck) and was able to place his $2,000 into the market every year at the lowest closing point. For example, Peter had $2,000 to invest at the start of 2001. Rather than putting it immediately into the market, he waited and invested on September 21, 2001—that year’s lowest closing level for the S&P 500. At the beginning of 2002, Peter received another $2,000. He waited and invested the money on October 9, 2002, the lowest closing level for the market for that year. He continued to time his investments perfectly every year through 2020.

- Ashley Action took a simple, consistent approach: Each year, once she received her cash, she invested her $2,000 in the market on the first trading day of the year.

- Matthew Monthly divided his annual $2,000 allotment into 12 equal portions, which he invested at the beginning of each month. This strategy is known as dollar-cost averaging. You may already be doing this through regular investments in your 401(k) plan or an Automatic Investment Plan (AIP), which allows you to deposit money into investments like mutual funds on a set timetable.

- Rosie Rotten had incredibly poor timing—or perhaps terribly bad luck: She invested her $2,000 each year at the market’s peak. For example, Rosie invested her first $2,000 on January 30, 2001—that year’s highest closing level for the S&P 500. She received her second $2,000 at the beginning of 2002 and invested it on January 4, 2002, the peak for that year.

- Larry Linger left his money in cash investments (using Treasury bills as a proxy) every year and never got around to investing in stocks at all. He was always convinced that lower stock prices—and, therefore, better opportunities to invest his money—were just around the corner.

The results are in: Investing immediately paid off

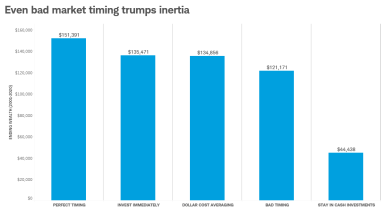

For the winner, look at the graph, which shows how much hypothetical wealth each of the five investors had accumulated at the end of the 20 years (2001-2020). Actually, we looked at 76 separate 20-year periods in all, finding similar results across almost all time periods.

Naturally, the best results belonged to Peter, who waited and timed his annual investment perfectly: He accumulated $151,391. But the study’s most stunning findings concern Ashley, who came in second with $135,471—only $15,920 less than Peter Perfect. This relatively small difference is especially surprising considering that Ashley had simply put her money to work as soon as she received it each year—without any pretense of market timing.

Matthew’s dollar-cost-averaging approach performed nearly as well, earning him third place with $134,856 at the end of 20 years. That didn’t surprise us. After all, in a typical 12-month period, the market has risen 75.6% of the time.3 So Ashley’s pattern of investing first thing did, over time, yield lower buying prices than Matthew’s monthly discipline and, thus, higher ending wealth.

Invested $2,000 annually in a hypothetical portfolio that tracks the S&P 500® Index from 2001-2020. The individual who never bought stocks in the example invested in a hypothetical portfolio that tracks the lbbotson U.S. 30-day Treasury Bill Index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur fees or expenses and cannot be invested in directly. The examples are hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. They are not intended to represent a specific investment product and investors may not achieve similar results. Dividends and interest are assumed to have been reinvested, and the examples do not reflect the effects of taxes, expenses, or fees. Had fees, expenses or taxes been considered, returns would have been substantially lower.

Rosie Rotten’s results also proved surprisingly encouraging. While her poor timing left her $14,300 short of Ashley (who didn’t try timing investments), Rosie still earned nearly three times what she would have if she hadn’t invested in the market at all.

And what of Larry Linger, the procrastinator who kept waiting for a better opportunity to buy stocks—and then didn’t buy at all? He fared worst of all, with only $44,438. His biggest worry had been investing at a market high. Ironically, had he done that each year, he would have earned far more over the 20-year period.

The rules generally don’t change

Regardless of the time period considered, the rankings turn out to be remarkably similar. We analyzed all 76 rolling 20-year periods dating back to 1926 (e.g., 1926-1945, 1927-1946, etc.). In 66 of the 76 periods, the rankings were exactly the same; that is, Peter Perfect was first, Ashley Action second, Matthew Monthly third, Rosie Rotten fourth and Larry Linger last.

But what about the 10 periods when the results were not as expected? Even in these periods, investing immediately never came in last. It was in its normal second place four times, third place five times and fourth place only once, from 1962 to 1981, one of the few periods of persistently weak equity markets. What’s more, during that period, fourth, third and second places were virtually tied.

Only 10 of 76 periods had unexpected rankings

| 20-year period | Perfect timing | Invested immediately | Dollar cost averaging | Bad timing | Never bought stocks |

| Expected rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1955-1974 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| 1958-1977 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 1959-1978 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 1960-1979 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 1962-1981 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 1963-1982 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 1965-1984 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 1966-1985 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 1968-1987 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 1969-1988 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

Ranking of ending amount of wealth after 20-year period. Rankings are hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

We also looked at all possible 30-, 40- and 50-year time periods, starting in 1926. If you don’t count the few instances when investing immediately swapped places with dollar cost averaging, all of these time periods followed the same pattern. In every 30-, 40- and 50-year period, perfect timing was first, followed by investing immediately or dollar cost averaging, bad timing and, finally, never buying stocks.

What this might mean for you

If you make an annual investment (such as a contribution to an IRA or to a child’s 529 plan) and you’re not sure whether to invest in January of each year, wait for a “better” time or dribble your investment out evenly over the year, be decisive. The best course of action for most of us is to create an appropriate plan and take action on that plan as soon as possible. It’s nearly impossible to accurately identify market bottoms on a regular basis. So, realistically, the best action that a long-term investor can take, based on our study, is to determine how much exposure to the stock market is appropriate for your goals and risk tolerance and then consider investing as soon as possible, regardless of the current level of the stock market.

If you’re tempted to try to wait for the best time to invest in the stock market, our study suggests that the benefits of doing this aren’t all that impressive—even for perfect timers. Remember, over 20 years, Peter Perfect amassed $15,920 more than the investor who put her cash to work right away.

Even badly timed stock market investments were much better than no stock market investments at all. Our study suggests that investors who procrastinate are likely to miss out on the stock market’s potential growth. By perpetually waiting for the “right time,” Larry sacrificed $76,733 compared to even the worst market timer, who invested in the market at each year’s high.

Consider dollar-cost averaging as a compromise

If you don’t have the opportunity, or stomach, to invest your lump sum all at once, consider investing smaller amounts more frequently. As long as you stick with it, dollar-cost averaging can offer several benefits:

- Prevents procrastination. Some of us just have a hard time getting started. We know we should be investing, but we never quite get around to it. Much like a regular 401(k) payroll deduction, dollar-cost averaging helps you force yourself to invest consistently.

- Minimizes regret. Even the most even-tempered stock trader feels at least a tinge of regret when an investment proves to be poorly timed. Worse, such regret may cause you to disrupt your investment strategy in an attempt to make up for your setback. Dollar-cost averaging can help minimize this regret because you make multiple investments, none of them particularly large.

- Avoids market timing. Dollar-cost averaging ensures that you will participate in the stock market regardless of current conditions. While this will not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss in a declining market, it will eliminate the temptation to try market-timing strategies that rarely succeed.

As you strive to reach your financial goals, keep these research findings in mind. It may be tempting to try to wait for the “best time” to invest—especially in a volatile market environment. But before you do, remember the high cost of waiting. Even the worst possible market timers in our studies would have beat not investing in the stock market at all.

In brief

- Given the difficulty of timing the market, the most realistic strategy for the majority of investors would be to invest in stocks immediately.

- Procrastination can be worse than bad timing. Long term, it’s almost always better to invest in stocks—even at the worst time each year—than not to invest at all.

- Dollar-cost averaging is a good plan if you’re prone to regret after a large investment has a short-term drop, or if you like the discipline of investing small amounts as you earn them.

1 In the hypothetical situation discussed in this article, the cost of waiting for the perfect moment to invest is quantified as the difference in ending amounts between waiting in cash and dollar-cost averaging. The benefit of perfect timing is quantified as the difference in ending amounts between perfect timing and dollar-cost averaging. The cost of waiting is therefore $90,418 and the benefit of perfect timing is $16,535.

2 All investors received $2,000 to invest before the first market open of each year. Investments were made using monthly data.

3 Study of 1,129 one-year periods, rolling monthly. First period is January 1926 to December 1926. Last period is January 2020 to December 2020.

Next Steps

Learn more about getting started in investing.

Explore the investment products Schwab offers.

Talk to us about the services that are right for you. Call us at 800-355-2162, visit a branch, find a consultant or open an account online.

Important Disclosures:

The information provided here is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation or personalized investment advice. The investment strategies mentioned here may not be suitable for everyone. Each investor needs to review an investment strategy for his or her own particular situation before making any investment decision.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to shifting market conditions. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed.

Examples provided are for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reflective of results you can expect to achieve.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results and the opinions presented cannot be viewed as an indicator of future performance.

Investing involves risk including loss of principal.

Diversification in a portfolio cannot ensure a profit or protect against a loss in any given market environment.

Periodic investment plans (dollar-cost-averaging) do not assure a profit and do not protect against loss in declining markets.

Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. For more information on indexes please see www.schwab.com/indexdefinitions.

The Schwab Center for Financial Research is a division of Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.