Hard to Handle: A Look at Hard vs. Soft Data

The "pandemicycle" (yes, that's a new term from us) has been unique in myriad ways; including multiple divergences within the economy. Divergences have occurred within the economy between goods and services, cyclical and noncyclical segments, and discretionary and nondiscretionary categories of spending; among others. A divergence we're tackling today is between soft and hard economic data. First, the definitions:

- Soft economic data refers to surveys, sentiment indicators, and expectations, such as consumer confidence, business outlook surveys, and Purchasing Managers' Indexes (PMIs).

- Hard economic data refers to measurable and objective metrics like gross domestic product (GDP), employment readings, retail sales, and industrial production.

A widely watched metric from Bloomberg is its Economic Surprise Index which tracks the difference between actual data releases and economists' forecasts. Bloomberg also separates them into hard data and soft data components, shown below.

Surprise!

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 1/17/2025.

Bloomberg "Hard Data" and "Soft Data" Surprise Indexes measure the difference between actual data and analysts' forecasts. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

There are a couple of interesting periods over the past decade, as shown above, including the surge in soft data surprises in 2017 (typically seen as tied to President Trump's win in late 2016). While hard data surprises did start to lift in late 2017, they remained well below soft data surprises throughout 2017 and 2018. Fast forward to the pandemic, another stark divergence opened up—again in favor of soft data surprises—as the economy started to find its footing in the latter part of 2020 into 2021.

Given elevated recession concerns, alongside a bear market in stocks in 2022, soft data surprises played catch-down to hard data surprises—ultimately with a couple of meaningful divergences in favor of the hard data in 2023 and 2024. Interestingly, although there has been a recent lift in soft data surprises, for now it pales in comparison to what occurred during the post-2016 election period.

Small business optimism on fire

As noted, there is a more muted increase in soft data surprises relative to Trump's prior win, where we have seen an historically significant surge in small businesses' outlook for "general business conditions" per the latest monthly data out of the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), as shown below.

Small business optimism on a tear

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), as of 12/31/2024.

NFIB also breaks out its data into soft and hard components, as shown below. Clearly the parabolic spike in optimism among the soft components has swamped what has been a generally lower trend for the hard components. The most recent uptick in optimism around the hard data bears watching as it would be a more palatable way for the divergence to correct than if optimism around the soft data turns out to be less grounded in reality.

Soft leapfrogs hard

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, NFIB (National Federation of Independent Business), as of 12/31/2024.

Hard and soft represents the sum of their respective components.

Inflation remains in focus

Divergences have abounded within inflation data, as mentioned; including between official estimates and consumers' expectations. Shown below via the blue line is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) one-year inflation expectations over time. From a peak of nearly 7% in 2022, expectations have been trending lower ever since, albeit with a flatter trend over the past few months. Conversely, although consumers' inflation expectations (via University of Michigan's Consumer Sentiment report) never reached the height of FRBNY's, there has been a notable shift up recently. The yellow line shows the skittishness of consumers' expectations given three bouts of sharp acceleration over the past two years.

Consumers skittish re: inflation

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, University of Michigan (UMich), as of 12/31/2024.

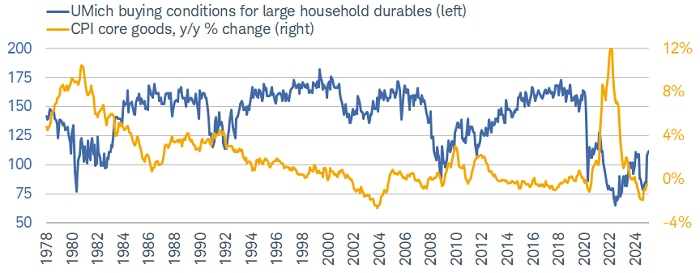

If a textbook case existed for the bout of inflation we endured a few years ago, the closest one would be the experience in the 1970s and early 1980s—especially on the goods side of the economy. Of course, no two periods are the same (which rings true for any chart looking at inflation), but as shown in the chart below, core goods inflation—in year-over-year (y/y) terms—reached a peak of 10.5% in 1974. At the same time, and as expected, consumers' perceptions of buying conditions for large household durable goods plummeted.

A similar dynamic unfolded in 2021 and 2022. Yet, the rebound in confidence has not been strong. In fact, core goods inflation is back to pre-pandemic levels, yet consumers still feel that buying conditions are as bad as they were at some points in the financial crisis and/or in the depths of the pandemic lockdown phase. Contrast that with the early 1980s: by the time core goods inflation returned to its pre-spike level, confidence had rebounded completely.

Not-so-good time for goods

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Bureau of Labor Statistics, University of Michigan (UMich), as of 1/15/2025.

Perhaps that's because a slew of modern-day consumers haven't experienced a significant inflation surge in their lifetime, or because the spike from the low in 2020 to the high in 2022 was much larger in percentage-point terms (-1.1% to +12.3%) compared to decades ago. Regardless, the massive shift in price levels over a relatively short timeframe is likely the main culprit, in our opinion.

Not only that, but there isn't yet confidence (from the Federal Reserve or consumers) that broader measures of inflation are settling back to pre-pandemic averages. That is evident when looking at the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Producer Price Index (PPI), shown below. While inflation has certainly made progress from peaks of nearly 10% (for CPI) and nearly 12% (for PPI), price pressures have bounced back of late, not yet settling in a zone consistent with the Fed's 2% target.

A higher inflation floor?

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of 12/31/2024.

Given the surge in pricing on both the consumer and producer sides, that means businesses have not been immune to the decline in confidence over the past few years. That has been evident across myriad surveys, especially the manufacturing outlook that comes from the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank (PFRB).

As shown below, PFRB survey respondents reported (on a net basis) a contraction in activity for nearly the entire period from the summer of 2022 through the winter of 2023. While they also reported an easing in price pressures (shown via the yellow line), that clearly wasn't good enough to lift overall confidence—until recently. The January report showed a hyperbolic increase in firms' perceptions of current business conditions; it was the second-largest increase on record, and somewhat consistent with the aforementioned NFIB outlook spike.

Getting sunny in Philadelphia

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 1/16/2025.

Whether the move was driven by politics or not, we don't think it should be extrapolated at this stage. First, even if it is tied to the change in the administration, there aren't any concrete results manufacturers can analyze yet—not least because the survey data was collected before the inauguration. Second, the region surveyed is quite small—encompassing the southern half of New Jersey, the eastern half of Pennsylvania, and Delaware—which means it is not at all representative of the whole country.

The latter point matters when looking at the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) Manufacturing Index, which has much broader, national coverage. As shown below, the index has been below 50 (in contraction) in every month since November 2022 except one (March 2024). That hasn't been consistent with a marked drop in industrial production (ISM's hard data counterpart), though. Year-over-year growth has been stubbornly stable around 0% for the better part of the past two years. In and of itself, that isn't great, but when overlaying the soft data (from ISM), one would think the decline would be much worse.

Still in a soft (data) patch

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 12/31/2024.

If anything, a coming recovery in soft data would likely be warranted, considering the hard data's resilience. With the economy growing at a respectable pace over the past couple years, it's clear that the persistent malaise in several soft data metrics hasn't been fully justified. Of course, the initial decline made sense given the sour inflation backdrop, but any coming rebound in the soft data should be treated as a catch-up, not a sign of an impending economic boom.

In sum

This "pandemicycle" has been disorienting in many ways, especially when it comes to the relationship between hard and soft economic data. Whether survey-based indicators have lost their touch is still up for debate—and probably a question that only applies to this unique cycle. Eventually, we think they'll reassert their importance and reliability; but the pandemic-driven gap needs to close, hopefully in favor of the hard data. Admittedly, for now, trends will likely remain murky and volatile in the near-term, given the mix of post-election hype and policy reality.