Time of the Season … For Year-End Targets

Key takeaways

- Year‑end S&P 500 targets focus on a single calendar day, thus ignoring market volatility, regime changes, and the path investors actually experience throughout the year.

- Strategists' forecasts tend to cluster not due to insight but due to career risk and herd behavior, resulting in targets that are routinely revised to chase the market rather than anticipate it.

- Investors are better served by focusing on risk‑reward dynamics, dispersion, policy shifts, and what's happening beneath the index surface—not on a single, calendar‑based price target.

The turn of the calendar to a new year brings a tradition on Wall Street during which sell-side firms' strategists issue their year-end price targets for the S&P 500. We're not sure exactly why the topic is "hotter" this year, but we've been fielding more than the usual number of questions about why we don't join the pack and issue our own year-end forecasts.

I (Liz Ann) will never forget a conversation I had with Chuck Schwab in 2000 in the immediate aftermath of Schwab's acquisition of U.S. Trust, at which I was a senior portfolio manager. When Chuck and I were chatting about Schwab's creation of the role of Chief Investment Strategist—a role I've had since then—he specifically mentioned the distaste he had for the year-end price target exercise; somewhat simply because it's a form of market-timing that's impossible to do consistently well. It was music to my ears.

A "shunful" exercise

There are myriad reasons for us shunning the exercise. Perhaps most important is that the stock market doesn't move toward a destination; it traverses a path of uncertainty and instability. A single year-end forecast ignores: volatility along the way, interim drawdowns that matter to real investors, and multiple plausible regimes (soft landing, hard landing, reacceleration, policy errors, geopolitics, etc.).

Most year-end price targets are essentially reverse-engineered and/or backed into from assumptions … not discovered: "If earnings grow by X% and the price/earnings (P/E) multiple is Y, then the index must be Z." That assumes that earnings estimates won't change (they always do), that multiples are stable (they're not—especially when rates move), and that macro surprises conveniently cooperate (they don't). Targets aren't really forecasts; they're algebraic identities dressed up as insight.

Year-end targets implicitly assume continuity—that tomorrow looks roughly like today. But the largest market moves often come from discontinuities; e.g., inflation rising or falling, monetary or fiscal policy turning on a dime, tightening financial conditions breaking something, earnings breadth deteriorating even as the index continues to rise, etc. By construction, year-end price targets can't capture regime changes—only extrapolation.

Targets often confuse accuracy with usefulness. A strategist could be "right" on a December 31 close and still be somewhat useless to investors who had to endure significant drawdowns, sharp sector rotations, dispersions between large cap and small cap performance, etc. A year like 1987 is a perfect example. The S&P 500 started the year at 242 and ended the year at 247. A strategist with a year-end target that was very close to the price at the start of the year would have been "right." But of course, the path along the way toward a flattish return for the year was anything but stable. The S&P 500 was up nearly 40% by late-August that year before rolling over and then imploding to the tune of -23% on the single day now known as Black Monday, followed by a range-bound market into year-end.

A bunch of strategists

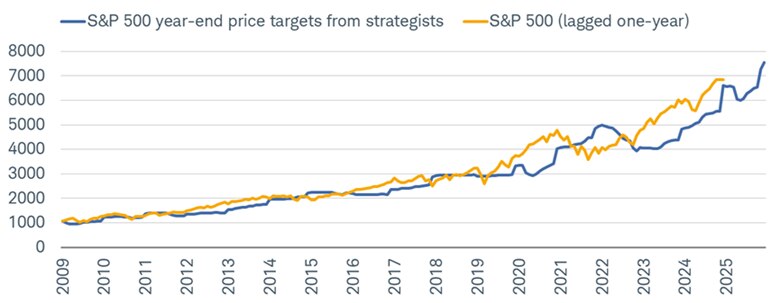

Wall Street targets tend to bunch together—not because consensus is insight, but because career risk often dominates forecast risk. Too bearish = client relationships suffer. Too bullish = credibility suffers. Within the pack = safe, defensive, forgettable. The result is herding disguised as wisdom. In addition, by February each year, most year-end targets are already obsolete; yet they're rarely revised meaningfully. In reality, as shown below, they are adjusted largely in response to what the market is doing along the way.

Follow the leader (market)

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 12/31/2025.

The average year-end price target for the S&P 500 Index is compiled from a survey of Wall Street strategists by Bloomberg reporters. Forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only, may be based upon proprietary research and are developed through analysis of historical public data. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

History lesson

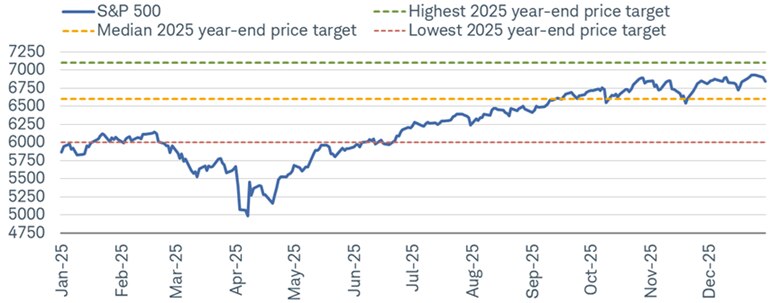

A look at last year is a useful and important use case for why year-end price targets are mostly reflections of the current state of market affairs—or in other words, pardon the pun, moving targets. Shown below is the S&P 500 for the full year of 2025. The dashed lines indicate the median (yellow), highest (green) and lowest (red) year-end estimates from Wall Street strategists surveyed by Bloomberg at the beginning of the year. As you can see, the median and highest estimates weren't far off from where the market ended up at its final close of the year. The lowest estimate looked spot on for most of the first quarter but ended up being too pessimistic as the market continued to rebound from the April lows.

That brings up an important point, though. As the S&P 500 plunged into bear market territory (on an intraday basis) in April, strategists cut their estimates swiftly and sharply. When the May Bloomberg survey came out, the median year-end estimate fell to 6,001 (from 6,570 in January). As the market rebounded, estimates followed: by October, the median survey estimate rose back up to 6,538–virtually unchanged from the beginning of the year.

So, by the end of the year, even the highest original price target wasn't that extreme or far from the S&P 500's ultimate destination. Of course, in the depths of the April selloff, that target looked wildly out of touch with tariff realities at the time, but we only know that with the benefit of hindsight.

Moving targets

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 12/31/2025.

The average year-end price target for the S&P 500 Index is compiled from a survey of Wall Street strategists by Bloomberg reporters. Forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only, may be based upon proprietary research and are developed through analysis of historical public data. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Last year's price-target races to both the bottom and top underscore the reality of those estimates essentially being an exercise in psychology. As human beings, we all (at some point) find ourselves over-indexing a particular moment in time (e.g., "Liberation Day"). It reminds us of an adage coined by our friend and veteran market observer, Helene Meisler: "Nothing like price to change sentiment."

In sum

Year-end S&P 500 price targets persist not because they're consistently informative, but because they're simple, quotable, easy to measure … and, simply, expected. They provide the illusion of certainty, a veneer of accountability, and a headline-friendly number. The rub is that the stock market is probabilistic, path-dependent, and regime-driven. Compressing that complexity into a single calendar-based price target isn't just unhelpful, it's misleading.

The real questions investors should care about are: What is the risk-reward from here? Where is dispersion and correlation rising or falling? Which assets benefit if inflation, economic growth, or fiscal/monetary policy surprises? What is happening beneath the headline S&P 500 index? Year-end price targets dodge those harder, but more useful, questions. Investors don't experience the market as a calendar endpoint. They experience it day-by-day and decision-by-decision.